Investor education series: Direct private equity investing #1

- Written by Toby Kelly

- Published on

This series of articles aims to give investors a taste for the different measurement methods that professionals use, what some reputable historical studies say might be reasonable returns for this asset class and some tips on how to create a portfolio with the best chance of achieving them.

Blog 1 of 3: Calculating returns on private equity investments

Over the last few years, growth in New Zealand's online investment industry has made keen investors ask the question "what kind of returns will I get from private company equity investments?" This can be tricky to answer particularly when looking at fast-growing companies who are often not yet profitable because any returns can be too early to predict and by that nature, difficult to estimate. Private company investing has some characteristics that make it quite different than from investing on the stock market. The investments are illiquid and infrequently priced, with the companies themselves typically earlier in their lifecycle and smaller in size than those on the stock market. They're also more likely to have managers as major shareholders, have less formal financial information and disclosures required, and are freer to pursue a long-term vision than public companies.

Return multiple

The nature of illiquidity means investments in private companies can only be made at specific points in time. For instance, when the company is either raising capital or selling some of its existing shareholding to outside investors. This creates a single upfront cost from the investment, and eventually if the company is sold, listed or the investor otherwise disposes of their shares, investors receive a single tranche of return all at once. This nature has led to the most basic return methodology - the multiple on invested capital. For example, if you invested $10,000 in a private company and five years later when the company is sold to a larger player in their industry, its shares have increased in price by 300 percent from your original purchase price, then you would receive a three times multiple return on your investment. The benefits of this method are that it's easy to understand and calculate. The negatives are that it doesn't consider the passage of time and therefore becomes more complicated across a portfolio of investments, particularly when you have different entry and exit points over your investing life. For example, a company may return two times your capital invested in just one years' time, which may be more preferable for some than a company which returns three times on investment, but over a four-year horizon.

Internal rate of return

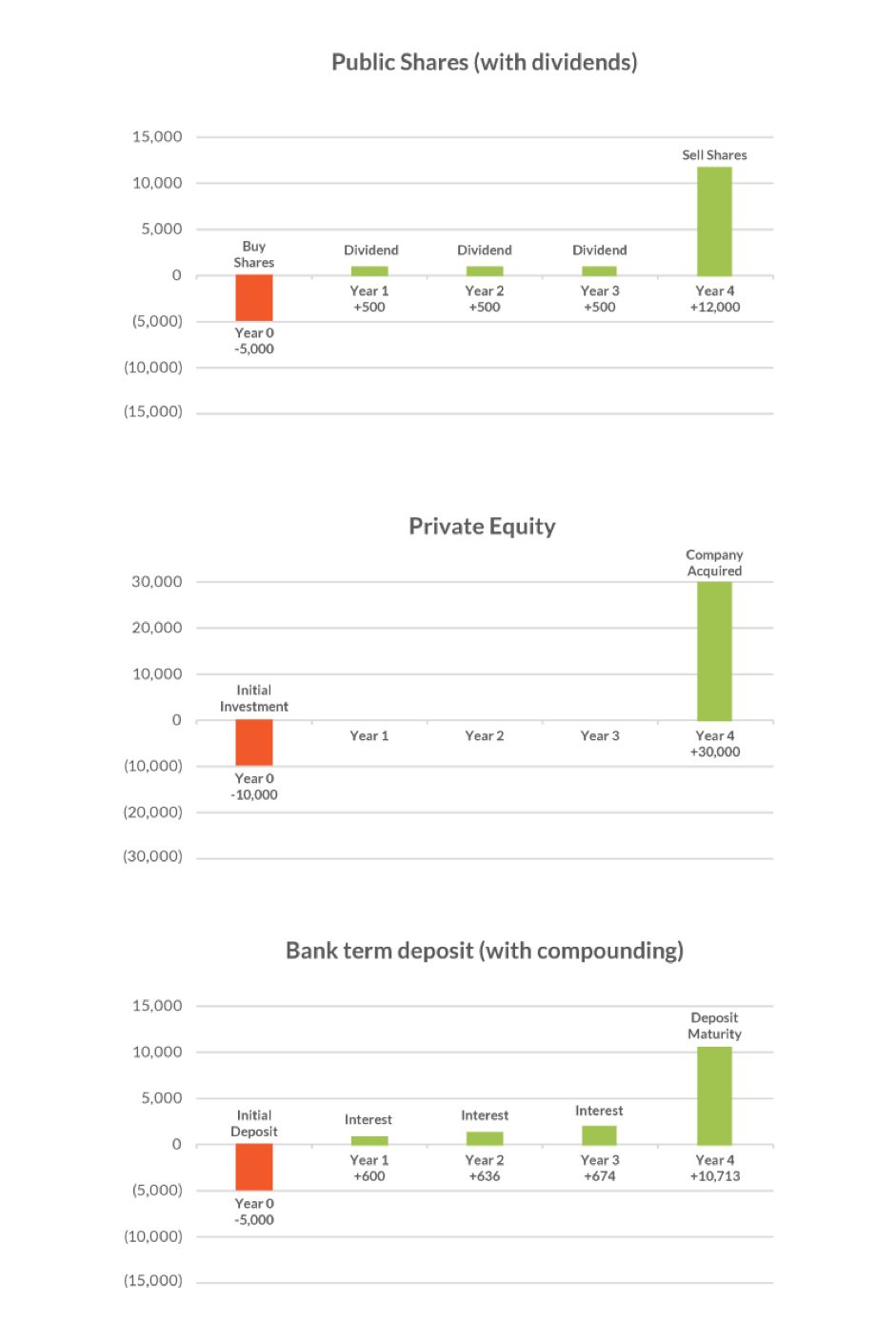

This leads us to the concept of IRR, or internal rate of return. The IRR can be thought of like an "interest rate" that accounts for all of the money that you put into an investment and all of the money you get back over time. IRR allows you to effectively spread out the "returns" from a capital gains asset class like private equity over the life of the investment so that it can be compared to other asset classes. This has obvious benefits to a private company investor when comparing multiple private investments, or different asset classes and is often best understood through a visual timeline of an indicative investment account in several asset classes:

The above account has made three investments in different asset classes. The public stocks have paid a dividend each year and are able to be sold at a premium, generating an IRR of about 8 per cent. The private company investment returns no dividend but generates a strong capital gain when the company is acquired, delivering an IRR of 31 per cent. The bank deposit earns interest, which if reinvested compounds over time to deliver a return of 6.5 per cent. An IRR calculation allows an investor to more fairly compare the performance of these assets with each other over time.

To recap, the IRR is useful because it takes into account the time and resulting illiquidity involved with private company investing, and makes the return on these investment portfolios comparable to more traditional ones like a term deposit or returns from an equity fund. The negatives of the IRR are the complexities in calculating it and the assumption it makes around the ability to reinvest any cash flows you receive back at the same return rate as the IRR calculated. However, this concern is the same for everyone using IRR (as it is the industry standard), and so for private company investors it gives them the best chance of comparing their own individual performance to that of the pros.